Thursday Trivia~The power of incentives

Thursday Trivia ~ 2nd Boxing Day Test match told us what Investors have been telling us since decades!

January 8, 2021Thursday Trivia – Why I am not happy with a 100 bagger stock

December 1, 2022

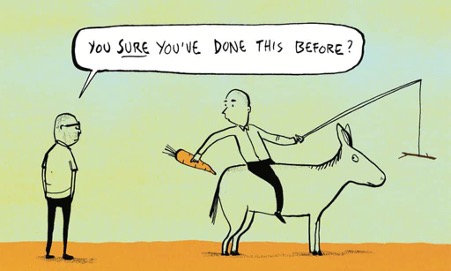

Many of us would have seen the recent performance of Pankaj Tripathi in the movie “Sherdil”. It’s a decent watch on Netflix. The film is about how the main character plans to get himself killed by a tiger for government compensation. Actual events from the Pilibhit area inspire it. The movie reflects on an essential aspect of the power of incentives and how they can change behaviours and outcomes.

Early in the history of Xerox, Joe Wilson, who was then in the government, had to go back to Xerox because he couldn’t understand how their better, new machine was selling so poorly in relation to their older and inferior machine. Of course, when he got there, he found out that the commission arrangement with the salesmen gave a tremendous incentive to the inferior machine.

There are many such stories worldwide where phenomenal outcomes have been achieved with the right incentive. The opposite also results in lost opportunities.

One of Munger’s favourite examples is how compensation structure was the innovation that first enabled FedEx to offer overnight delivery. In this case, a minor incentive misalignment was the barrier to the success of what is now a ~$50B company.

The integrity of the Federal Express system requires that all packages be shifted rapidly among airplanes in one central airport each night. And the system has no integrity for the customers if the night work shift can’t complete it’s assignment fast. FedEx had one hell of a time getting the night shift to do the right things. They tried moral suation. They tried everything in the world without luck.

Finally, someone got the happy thought that it was foolish to pay the night shift by the hour when what the employer wanted was not maximized billable hours of employee service but fault-free, rapid performance of a particular task. Maybe, this person thought, if they paid the employees per shift and let all the night shift employees go home when all the planes were loaded, the system would work better. And that solution worked.

One small change in compensation, one huge result in output.

Hence one of the most admired brains on the planet, Charlie Munger, goes on to say

“Never, ever, think about something else when you should be thinking about the power of incentives.”

This incentive anomaly is particularly true for us as consumers and as investors. There have been several pieces of evidence of how certain products are pushed and sold because they tend to give better incentives to the intermediary. Take this 2013 article, for example,

Unit-linked insurance plans take a beating

From more than 70% of sales during 2008-09, the share of Ulips in new business premium dropped to a mere 15% in the last financial year

In 2010 IRDA reduced the commissions and fees charged by insurance companies on ULIP products. This was because of huge cries against the mis-selling of ULIPs. After this change, ULIPs became unpopular. A leading insurance company which had never designed a traditional life insurance policy in the decade of its existence introduced them in that year. The irony is traditional plans continue to charge the same expenses as they were in ULIPs, only now it’s not visible to the policyholder.

Similarly, you would have heard about products like PMS (Portfolio Management Service) and AIF (Alternate Investment Funds). These are popular products favoured by HNIs. Only after ten years of its launch, AIF is now a bigger industry than PMS. While some say that the diversity and flexibility provided by AIFs may be the reason, I firmly believe that it has to do with incentive structure. AIFs are the only equity products available now where the provider can pay upfront commissions, resulting in the growth of assets by seven times only in the last five years.

So how can you, as an investor, use the power of incentive in your favour? Fortunately, SEBI considered this and introduced the RIA(Registered Investment Advisor) framework for transparent advice and mutual fund direct plans. Simply put, you can use the services of an RIA where no commissions are paid. All revenues of RIAs are the fees paid by the clients directly to them. This massively changes the playing field in favour of investors. Instead of pushing a product to the Investor for commission, the Investor can pay intermediaries benefitting from the advice and the value provided.

SEBI introduced RIA regulations and Direct plans in 2013. These are still not well known. One of the reasons may be that paying fees inflicts pain, which is entirely invisible in commission-based transactions. But if you look at it from the power of incentive, it’s a great option.

It should not be construed that commission-based investments are always biased and not in investors’ best interest. I know some of the Mutual Fund Distributors who are phenomenal in what they do. Fee, as I mentioned, is a mighty tool that gives you transparency and an incentive structure that helps align the interest of the advisor and the Investor.

Your comments and feedback are highly appreciated. Happy Investing!